What are our screens and devices doing to us? Psychologist Adam Alter has spent the last five years studying how much time screens steal from us and how they're getting away with it. He shares why all those hours you spend staring at your smartphone, tablet or computer might be making you miserable -- and what you can do about it.

Wednesday, May 29, 2019

Thursday, May 23, 2019

Twelve Ideas for Student Activities This Summer

|

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

What you should know about Vaping and e-cigarettes

"E-cigarettes and vapes have exploded in popularity in the last decade, especially among youth and young adults -- from 2011 to 2015, e-cigarette use among high school students in the US increased by 900 percent. Biobehavioral scientist Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin explains what you're actually inhaling when you vape (hint: it's definitely not water vapor) and explores the disturbing marketing tactics being used to target kids. "Our health, the health of our children and our future generations is far too valuable to let it go up in smoke -- or even in aerosol," she says."

Tuesday, May 14, 2019

"Jerry Mintz has been a leading voice in the alternative school movement for over 30 years. In addition to his seventeen years as a public and independent alternative school principal and teacher, he has also helped found more than fifty public and private alternative schools and organizations. He has lectured and consulted in more than twenty-five countries around the world.

In 1989, he founded the Alternative Education Resource Organization and since then has served as it’s Director. Jerry was the first executive director of the National Coalition of Alternative Community Schools (NCACS), and was a founding member of the International Democratic Education Conference (IDEC)."

What makes me smile is the type of education that Jerry Mintz and many other educational thinkers are advocating for is not alternative, but is based around how we learn most effectively as humans. The alternative system is the one that was introduced in Church schools in the 15th Century, expanded again at the time of the agricultural revolution in the 18 Century and finally set in stone by the Prussians and the Committee of 10 for the post industrial revolution world of the 19th Century. The system we have today is based around obedience, compliance and subjugation to a higher authority. Is this what we want for our children and their future?"

How Early Academic Training Retards Intellectual Development

"Academic skills are best learned when a person wants them and needs them."

In my last post I summarized research indicating that early academic training produces long-term harm. Now, in this post, I will delve a bit into the question of how that might happen.

It's useful here to distinguish between academic skills and intellectual skills—a distinction nicely made in a recent article by Lillian Katz published by the child advocacy organization Defending the Early Years

Academic skills are, in general, tried and true means of organizing, manipulating, or responding to specific categories of information to achieve certain ends. Pertaining to reading, for example, academic skills include the abilities to name the letters of the alphabet, to produce the sounds that each letter typically stands for, and to read words aloud, including new ones, based on the relationship of letters to sounds. Pertaining to mathematics, academic skills include the ability to recite the times tables and the abilities to add, subtract, multiply, or divide numbers using learned, step-by-step procedures, or algorithms. Academic skills can be and are taught directly in schools, through methods involving demonstration, recitation, memorization, and repeated practice. Such skills lend themselves to objective tests, in which each question has one right answer.

Intellectual skills, in contrast, have to do with a person’s ways of reasoning, hypothesizing, exploring, understanding, and, in general, making sense of the world. Every child is, by nature, an intellectual being--a curious, sense-making person, who is continuously seeking to understand his or her physical and social environments. Each child is born with such skills and develops them further, in his or her own ways, through observing, exploring, playing, and questioning. Attempts to teach intellectual skills directly inevitably fail, because each child must develop them in his or her own way, through his or her own self-initiated activities. But adults can influence that development through the environments they provide. Children growing up in a literate and numerate environment, for example—such as an environment in which they are often read to and see others read, in which they play games that involve numbers, in which things are measured and measures have meaning—will acquire, in their own ways, understandings of the purposes of reading and the basic meaning and purposes of numbers.

Now, here’s the point to which I’m leading. It is generally a waste of time, and often harmful, to teach academic skills to children who have not yet developed the requisite motivational and intellectual foundations. Children who haven’t acquired a reason to read or a sense of its value will have little motivation to learn the academic skills associated with reading and little understanding of those skills. Similarly, children who haven’t acquired an understanding of numbers and how they are useful may learn the procedure for, say, addition, but that procedure will have little or no meaning to them.

The learning of academic skills without the appropriate intellectual foundation is necessarily shallow. When the drill stops—maybe for summer vacation—the skills are quickly forgotten. (That’s the famous “summer slide” in academic ability that some educators want to reduce by keeping children in school all year long!) Our brains are designed to hold onto what we understand and to discard nonsense. Moreover, when the procedures are learned by rote, especially if the learning is slow, painful, and shame-inducing, as it often is when forced, such learning may interfere with the intellectual development needed for real reading or real math.

Rote-trained, pained children may lose all desire to play with and explore literary and numerical worlds on their own and thereby fail to develop the intellectual foundations for real reading or math. This explains why researchers repeatedly find that academic training in preschool and kindergarten results in worse, not better, performance on academic tests in later grades (see here). This is also why children’s advocacy groups—such as Defending the Early Years

In the remainder of this post, I review some findings, discussed in earlier essays in this blog, that illustrate the idea that early academic training can be harmful and that academic learning comes easily once a person has acquired the requisite intellectual foundation and wants to learn the academic skills.

Example 1—Benezet’s experiment showing the harm of math training in grades 1 - 5

A remarkable experiment (previously described here) that has been completely ignored by the educational world was performed in the 1930s, in Manchester, New Hampshire, under the direction of the then-superintendent of Manchester schools, L. P. Benezet.[1] In the introduction to his report on the study, he wrote, “For some years I had noted that the effect of the early introduction of arithmetic had been to dull and almost chloroform the child’s reasoning facilities.” All that drill, he claimed, had divorced the whole realm of numbers and arithmetic, in the children’s minds, from common sense, with the result that they could do the calculations as taught to them, but didn’t understand what they were doing and couldn’t apply the calculations to real life problems. Using the terminology I’ve introduced in this essay, we could say that the children learned the academic skills, by rote, without relating them to an intellectual understanding of numbers and their purposes.

As a result of this observation, Benezet proposed an experiment that even in the 1930s seemed outrageous. He asked the principals and teachers in some of the schools located in the poorest parts of Manchester to drop arithmetic from the curriculum of grades 1 through 5. The children in those classrooms would not be given any of the usual lessons in adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing until they reached sixth grade. He chose schools in the poorest neighborhoods because he knew that if he tried to do this in wealthier neighborhoods, where the parents were high school or college graduates, the parents would rebel.

As part of the plan, he asked the teachers to devote the time that they would normally spend on arithmetic to class discussions, in which the students would be encouraged to talk about any topics that interested them—anything that would lead to genuine, lively communication. This, he thought, would improve their abilities to reason and communicate logically and would also be enjoyable. He also asked the teachers to give their pupils some practice in measuring and counting things, to assure that they would have some practical experience with numbers.

In order to evaluate the experiment, Benezet arranged for a graduate student from Boston University to come up and test the Manchester children at various times in the sixth grade. The results were remarkable. At the beginning of their sixth grade year, the children in the experimental classes, who had not been taught any arithmetic, performed much better than those in the traditional classes on story problems that could be solved by common sense and a general understanding of numbers and measurement. Of course, at the beginning of sixth grade, those in the experimental classes performed worse on the standard school arithmetic tests, where the problems were set up in the usual school manner and could be solved simply by applying the rote-learned algorithms. But by the end of sixth grade those in the experimental classes had completely caught up on this and were still way ahead of the others on story problems.

In sum, Benezet showed that children who received just one year of arithmetic, in sixth grade, performed at least as well on standard school calculations and much better on math story problems than kids who had received six years of arithmetic training. This was all the more remarkable because of the fact that those who received just one year of training were from the poorest neighborhoods--the neighborhoods that had previously produced the poorest test results.

What a finding! Benezet showed that five years of tedious (and for some, painful) drill could simply be dropped, and by dropping it the children did better, in sixth grade, than did those who had endured the drill for five previous years. This is the kind of finding that educators regularly choose to ignore. If they paid attention to such findings they would do themselves out of their jobs, because the truth is, what Benezet found for math can occur for every subject. Young people learn amazingly rapidly, and require little help, when they learn what they want to learn, in their own ways, on their own time.

Today educators who want to reduce the gap between rich and poor in academic learning are pushing for earlier and earlier academic training, especially for the poor. But Benezet's study, and other studies too, suggest that the better way to reduce the gap, and to improve learning overall, would be to start academic training later, not earlier--maybe much later.

Example 2: Preparing for the math SAT, at Sudbury Valley School, after no previous study of math

Here’s an observation that tops even Benezet’s, though it is not the result of a formal experiment. In previous posts (here and here) I have described the Sudbury Valley School, located in Framingham, Massachusetts. It is a school that accepts students from age 4 on through high school age, does not separate students by age, does not offer a curriculum, does not evaluate students in any formal way, and allows students to take full charge of their own education. Each student pursues his or her own interests in his or her own ways. Follow-up studies of the graduates show that they do very well in life. Here’s the story about math at SVS that I told in a previous post:

“To find out more about how kids with no formal math training deal with college admissions math, I interviewed Mikel Matisoo, the Sudbury Valley staff member who is most often sought out by students who want help in preparing for the math SAT. He told me that the students who come to him are usually those who have relatively little long-term interest in math; they just want to do well enough on the SAT to get into the college of their choice. He said, "The way the SAT is structured it is relatively easy to prepare directly for it; there are certain tricks for doing well." Typically, Matisoo meets with the students for about 1 to 1 ½ hours per week for about six to ten weeks and the students may do another 1 to 1 ½ hours per week on their own. That amounts to a range of about 12 to 30 hours, total, of math work for students who may never before have done any formal math. The typical result, according to Matisoo, is a math SAT score that is good enough for admission to at least a moderately competitive college. Matisoo explained that the kids who are really into math, and who get the top SAT scores, generally don't seek him out because they can prepare on their own.”

By the time the students come to Matisoo for help with the SAT they have been living for roughly 16 to 18 years in a world of numbers. They have picked up, in the course of life, the “survival math” that we all use in daily life, the kind that you and I remember because we use it regularly. Given that foundation, and the fact that they have done many things on their own that involve abstract thinking, with our without numbers, and the fact that they are motivated to do well on the SAT, they can easily learn what they must for the goal they have in mind. All that drill, not just in grades 1-5 as Benezet found, but in grades 1-12, is unnecessary. When young people are intellectually well prepared to learn the math skills and have a reason to do it, the skills come remarkably easily.

Example 3: How unschooled and Sudbury-schooled children learn to read

In standard schools it is important to learn how to read by the schedule that the school dictates, because if you fail to do so you will be labeled as “slow,” or worse, and may develop a self-image as stupid. You may fall forever behind. But if you don’t go to a school of the sort where everyone must follow a predetermined track, you can learn to read anytime you want. And when that happens, learning to read is generally pleasant, relatively easy, and often hardly noticed even by the learner.

A few years ago I conducted a survey of unschooling families to find out when and how children who were not sent to school and were not subjected to a curriculum at home learned to read. You can look back to that report for the details, but here is a summary of the main conclusions:

(1) For non-schooled children there is no critical period or best age for learning to read. Some children learn very early (as early as age 3), others much later (as late as age 11 in this sample). The timing of such learning doesn’t seem to depend on general intelligence, but upon interest. Some children, for whatever reason, become interested in reading very early, others later.

(2) Motivated children can go from apparent non-reading to fluent reading very quickly. For motivated children, who are intellectually ready, learning to read requires none of the painful, slow drill that we regularly put children through in school. Many children pick it up without anything that looks like a lesson; others ask for some help, which may come in the form of a few lessons concerning the sounds of the letters.

(3) Attempts to push reading can backfire. Children (like all of us) resist being pushed into doing things they don’t want to do, and this applies to reading as much as to anything else.

(4) Children learn to read when reading becomes, to them, a means to some valued end. Children who want to read stories that nobody will read to them, or who want to find information only attainable through the written word, learn to read. Children on their own initiative rarely learn to read just for the sake of learning to read.

(5) Reading, like many other skills, is learned socially through shared participation. Children who can’t read often learn to read through being read to, or through playing games that involve reading with children who already know how to read.

(6) Some children become interested in writing before reading, and they learn to read as they learn to write. This is an illustration of the principle that children learn by doing. Writing is more obviously active than reading, and some children are drawn to it. They want to write their own stories, but in doing so they ask for help, and in getting that help they learn to read. The first things they read are their own stories.

(7) There is no predictable “course” through which children learn to read (or, for that matter, learn anything else). That, essentially, is why our schools, which are founded on the idea that all children can learn through the same course, at the same time, are such dismal failures.

----------

This essay started where the conversation is in our larger society—on the controversial topic of academic training in preschools and kindergartens. But it moved on to a bigger and more radical issue, that of whether we need schools for academic learning at all. A regular theme of this blog is that what our children really need are intellectually stimulating environments—environments where they can develop their intelligence in their own individual ways. For children growing up in such environments, the academic skills come quite easily, at just the times when they are needed, and require little if any help from teachers.

Tuesday, May 7, 2019

Screentime Is Making Kids Moody, Crazy and Lazy 6 Ways electronic screen time makes kids angry, depressed and unmotivated.

Source: pathdoc/fotolia

Children or teens who are “revved up” and prone to rages or—alternatively—who are depressed and apathetic have become disturbingly commonplace. Chronically irritable children are often in a state of abnormally high arousal, and may seem “wired and tired.”That is, they’re agitated but exhausted. Because chronically high arousal levels impact memory and the ability to relate, these kids are also likely to struggle academically and socially.

At some point, a child with these symptoms may be given a mental-healthdiagnosis such as major depression, bipolar disorder, or ADHD, and offered corresponding treatments, including therapy and medication. But often these treatments don’t work very well, and the downward spiral continues.

What’s happening?

Both parents and clinicians may be “barking up the wrong tree.” That is, they’re trying to treat what looks like a textbook case of mental disorder, but failing to rule out and address the most common environmental cause of such symptoms—everyday use of electronics. Time and again, I’ve realized that regardless of whether there exists any “true” underlying diagnoses, successfully treating a child with mood dysregulation today requires methodically eliminating all electronics use for several weeks—an “electronics fast”—to allow the nervous system to “reset.”

If done correctly, this intervention can produce deeper sleep, a brighter and more even mood, better focus and organization, and an increase in physical activity. The ability to tolerate stress improves, so meltdowns diminish in both frequency and severity. The child begins to enjoy the things they used to, is more drawn to nature, and imaginary or creative play returns. In teens and young adults, an increase in self-directed behavior is observed—the exact opposite of apathy and hopelessness. It’s a beautiful thing.

At the same time, the electronic fast reduces or eliminates the need for medication while rendering other treatments more effective. Improved sleep, more exercise, and more face-to-face contact with others compound the benefits—an upward spiral! After the fast, once the brain is reset, the parent can carefully determine how much if any electronics use the child can tolerate without symptoms returning.

Restricting electronics may not solve everything, but it’s often the missing link in treatment when kids are stuck.

But why is the electronic fast intervention so effective? Because it reverses much of the physiological dysfunction produced by daily screen time.

Children’s brains are much more sensitive to electronics use than most of us realize. In fact, contrary to popular belief, it doesn’t take much electronic stimulation to throw a sensitive and still-developing brain off track. Also, many parents mistakenly believe that interactive screen-time—Internet or social media use, texting, emailing, and gaming—isn’t harmful, especially compared to passive screen time like watching TV. In fact, interactive screen time is more likely to cause sleep, mood, and cognitive issues, because it’s more likely to cause hyperarousal and compulsive use.

Here’s a look at six physiological mechanisms that explain electronics’ tendency to produce mood disturbance: article continues after advertisement

Because light from screen devices mimics daytime, it suppresses melatonin, a sleep signal released by darkness. Just minutes of screen stimulation can delay melatonin release by several hours and desynchronize the body clock. Once the body clock is disrupted, all sorts of other unhealthy reactions occur, such as hormone imbalance and brain inflammation. Plus, high arousal doesn’t permit deep sleep, and deep sleep is how we heal.

Many children are “hooked” on electronics, and in fact gaming releases so much dopamine—the “feel-good” chemical—that on a brain scan it looks the same as cocaine use. But when reward pathways are overused, they become less sensitive, and more and more stimulation is needed to experience pleasure. Meanwhile, dopamine is also critical for focus and motivation, so needless to say, even small changes in dopamine sensitivity can wreak havoc on how well a child feels and functions.

3. Screen time produces “light-at-night.”

Light-at-night from electronics has been linked to depression and even suicide risk in numerous studies. In fact, animal studies show that exposure to screen-based light before or during sleep causes depression, even when the animal isn’t looking at the screen. Sometimes parents are reluctant to restrict electronics use in a child’s bedroom because they worry the child will enter a state of despair—but in fact removing light-at-night is protective.

Both acute stress (fight-or-flight) and chronic stress produce changes in brain chemistry and hormones that can increase irritability. Indeed, cortisol, the chronic stress hormone, seems to be both a cause and an effect of depression—creating a vicious cycle. Additionally, both hyperarousal and addiction pathways suppress the brain’s frontal lobe, the area where mood regulation actually takes place.

5. Screen time overloads the sensory system, fractures attention, and depletes mental reserves.

Experts say that what’s often behind explosive and aggressive behavior is poor focus. When attention suffers, so does the ability to process one’s internal and external environment, so little demands become big ones. By depleting mental energy with high visual and cognitive input, screen time contributes to low reserves. One way to temporarily “boost” depleted reserves is to become angry, so meltdowns actually become a coping mechanism.

Source: Chubykin Arkady/Shutterstock

6. Screen-time reduces physical activity levels and exposure to “green time.”

Research shows that time outdoors, especially interacting with nature, can restore attention, lower stress, and reduce aggression. Thus, time spent with electronics reduces exposure to natural mood enhancers.

In today’s world, it may seem crazy to restrict electronics so drastically. But when kids are struggling, we’re not doing them any favors by leaving electronics in place and hoping they can wind down by using electronics in "moderation." It just doesn't work. In contrast, by allowing the nervous system to return to a more natural state with a strict fast, we can take the first step in helping a child become calmer, stronger, and happier.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-wealth/201508/screentime-is-making-kids-moody-crazy-and-lazy?goal=0_286e03f42f-6ae56d13f7-288247817&mc_cid=6ae56d13f7&mc_eid=b39eab2bae

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-wealth/201508/screentime-is-making-kids-moody-crazy-and-lazy?goal=0_286e03f42f-6ae56d13f7-288247817&mc_cid=6ae56d13f7&mc_eid=b39eab2bae

Saturday, May 4, 2019

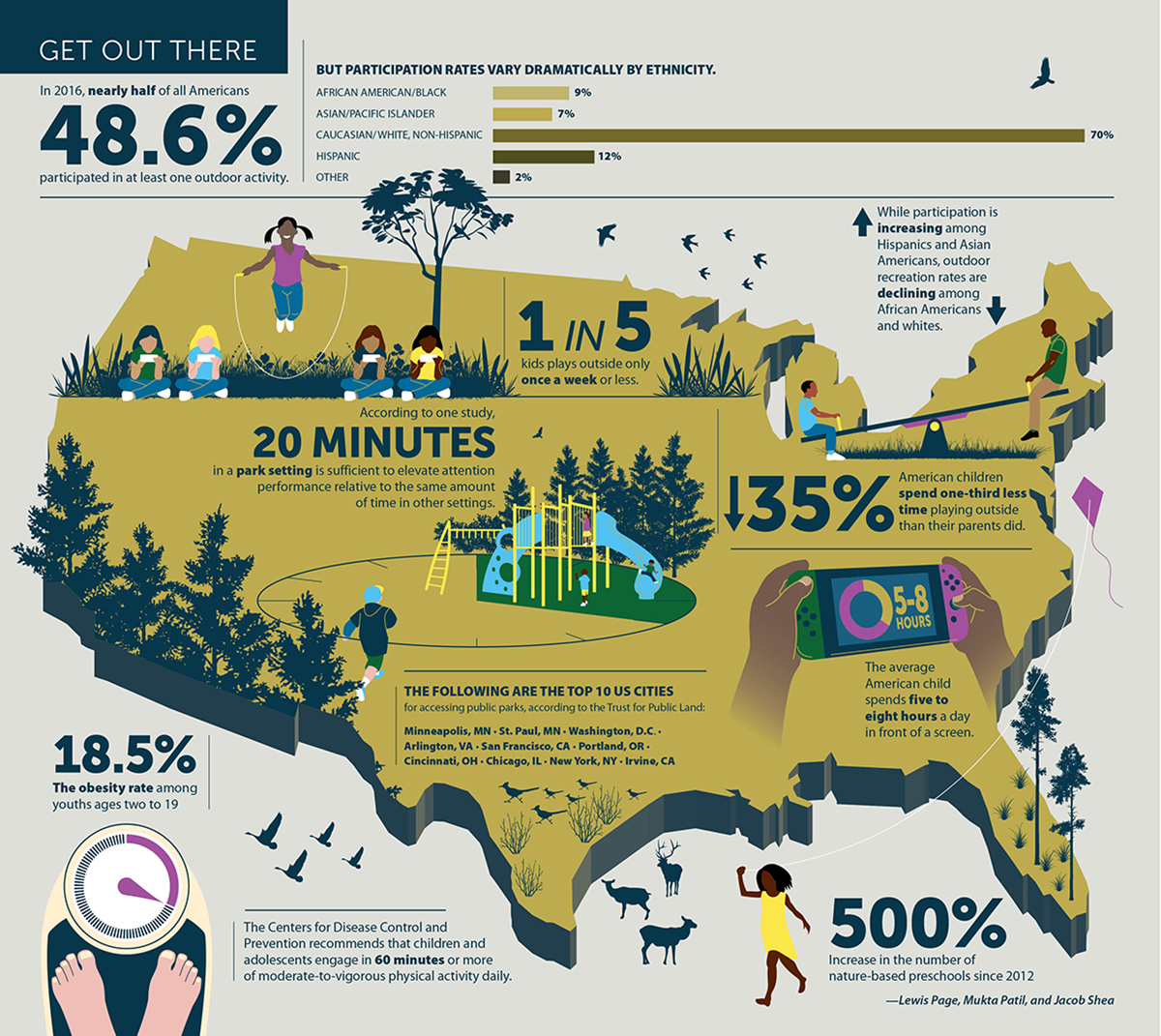

Outdoors for All....Access to nature should be a human right

BY RICHARD LOUV | APR 25 2019

A FEW YEARS AGO, pediatrician and clinical scientist Nooshin Razani treated a four-year-old girl whose family had recently fled Yemen and settled in the San Francisco Bay Area. The family had received news the night before that members of the father's family had been killed in a bombing back home. The child was suffering from anxiety. "I was thinking, 'I have nothing to give to this little girl. What can I give her?'" Razani says. The typical medical response would be to offer the girl some counseling and, if necessary, medication. Razani decided the patient needed an additional, broader prescription. She asked the girl and her parents if they would like to go to the park with her. "The expression on that child's face, the yearning for a piece of childhood, was deeply moving," the doctor recalls.

Razani is the founder of the Center for Nature and Health, which conducts research on the connection between time in nature and health and is the nation's first nature-based clinic associated with a major health provider, UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital in Oakland, California. The clinic collaborates with the East Bay Regional Park District to offer a program called Stay Healthy in Nature Everyday. Participating physicians share local park maps with their patients and offer family nature outings–70 of them so far. Often, the physicians will join the outings. Burned-out doctors need these experiences too, Razani says.

"We did a randomized study of the impact on the participating families," she says. "Every single park visit substantially reduced parent stress." In June 2018, the center began billing insurance companies for patient visits that include nature connection as part of the treatment. This was a breakthrough for the increasing number of US health care professionals who now prescribe nature or integrate it into their practices in other ways, including pediatrician Robert Zarr in Washington, D.C., who organized Park Rx America to encourage health providers around the country to do the same. Neither Razani nor Zarr considers time in nature a panacea, but both regularly witness its preventive and therapeutic effects, particularly on children and adults undergoing traumatic stress.

The increased popularity of incorporating the healing power of nature into health care, public health programs, architecture, and education has been inspired by a relatively new body of scientific evidence that associates improved wellness and lower mortality rates with access to green and biodiverse spaces. In the span of a decade, the number of studies indicating that time spent in natural surroundings–whether groomed urban parks or unruly wilderness landscapes–can improve people's well-being has increased from dozens to hundreds. In 2017, a study published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet Planetary Health suggested that people who live in green neighborhoods live longer than those with little nature nearby. The study tracked 1.3 million Canadian adults living in the country's 30 biggest cities and considered socioeconomic and education differences as control factors. Dan Crouse, a health geographer and the lead author of the study, told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, "There was a lot bigger effect than I think any of us had been expecting."

The psychological, physical, and cognitive benefits of nature connection may be universal, but access to natural areas is not.

Expanding research has also shown that exposure to nature can reduce children's symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and help prevent or reduce obesity, myopia, and vitamin D deficiency. And the research suggests that time spent in nature may improve social bonding and reduce violence, stimulate learning and creativity, help raise standardized test scores, and serve as a buffer to toxic stress, depression, and anxiety. Most of these findings are correlative, not causal. But longitudinal studies are beginning to support them.

The psychological, physical, and cognitive benefits of nature connection may be universal, but access to natural areas is not. Take the city of Oakland, where Razani practices. The neighborhoods with the most poverty are often those with the fewest parks and the least green space. "This is a social justice issue," she says. More than 90 percent of her clinic's patients are on Medi-Cal, living at or below the federal poverty line. Many suffer from a lack of nature access and from pollution in their immediate neighborhoods. According to a study published in Environmental Research, African American, Hispanic, and low-income children are most likely to be exposed to toxins at school. One reason is that school districts in less-affluent communities often place schools on cheaper land next to highways, factories, or contaminated sites. So teachers at such schools may be less likely to take their students outside to play or learn.

Every day, Razani witnesses the profound stress that urban families experience. She's seen families that lack the seemingly basic opportunity to spend time outside–parents who feel compelled to keep their children indoors because of neighborhood crime. "It's important not to assume that people with less income value nature less," Razani says. "This isn't a question of their values–it's about housing, about equal access to nature. . . . Some people get stuck on the idea that we need to teach people how to love nature. The truth is that people whose cultures were colonized often had more true nature connection in their histories than did the colonizers."

The concept of nature as a human right may sound radical, or like a dreamy fantasy. In a world in which millions of children are brutalized by war, hunger, and disease, can we spare time to advance a child's right to experience nature? For her part, Razani rejects the notion that equitable access to nature should be ranked lower in the hierarchy of human necessities. When her clinic takes in new patients, they're asked what they need most. Yes, housing, better food, and safety are on the list. But they also hunger for more nature in their lives.

Razani is not alone in making a rights-based claim on access to nature. A nascent global movement–made up of parents, educators, researchers, and health practitioners like Razani–insists that universal and equitable access to nature is fundamental to our humanity as well as to the future of life on Earth. Razani and others are making the case that nature connection should be recognized as a civil right–a human right.

This movement is grounded in biologist Edward O. Wilson's biophilia hypothesis–which suggests that human beings are genetically programmed to have an affiliation with the rest of nature–and anchored in ideals of justice and fairness. If Wilson is right, and if the research is correct, nature connection is more than a nice pursuit, a pastime, or a privilege. It is a necessity. In the words of David Orr, a leader in environmental education and green urban design, the human connection to a healthy natural environment is "the ultimate human right, upon which all other rights depend."

THE CONCEPT OF A HUMAN RIGHT to nature connection got its first major boost in September 2012, when Annelies Henstra, a Dutch human rights lawyer; Cheryl Charles, cofounder of the Children & Nature Network; and others made the case at the World Conservation Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Held in Jeju, South Korea, the conference attracted over 10,000 people, representing more than 200 governments and government organizations and more than 1,000 nongovernmental organizations. Through the leadership of Henstra, Charles, and Keith Wheeler, chair of the IUCN Commission on Education and Communication, the conference passed a historic resolution declaring that children have a human right to experience a healthy natural world. "That year, 2012, struck me as a pivotal year for the IUCN, in which a groundswell began to emerge within the organization to understand that if people don't connect to nature, beginning with children, that species, habitats, and ecosystems will be at increasing risk over time," Charles recalls. "This was a profound cultural shift . . . within the organization, as scientists and conservation leaders–who care passionately about wildlife and might just as soon keep people out of wild areas–were beginning to realize that people need to connect with nature personally in order to care about it."

The resolution, "Child's Right to Connect With Nature and to a Healthy Environment," begins by recognizing "the increasing disconnection of people and especially children from nature, and the adverse consequences for both healthy child development (nature deficit disorder) as well as responsible stewardship for nature and the environment in the future." The resolution goes on to state, "Growing up in a healthy environment and connecting children with nature is of such a fundamental importance for both children and the (future of) the conservation of nature and the protection of the environment, that it should be recognized and codified internationally as a human right for children."

Inspiring words, to be sure. But the IUCN delegates were determined that their grand rhetoric have real legal force behind it. The resolution called on the IUCN's membership to promote the inclusion of this right within the framework of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. That global treaty went into effect in 1990, and the countries that have ratified it are bound to its obligations through international law. (Every member nation of the UN has ratified it except the United States.) A Switzerland-based group, Terre des Hommes, which provides emergency relief and other health-related assistance to more than 3 million children and their families in more than 45 countries annually, is one of the organizations leading the effort to include access to nature in the existing UN agreement.

"The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is one of the very few human rights instruments to refer to the environment," says Jonas Schubert, the organization's human rights officer. Schubert, a veteran of maneuvering through the UN's complicated processes, says that there may be a few ways to establish access to nature as a kind of guaranteed right. He points out that David Boyd, the UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment, has already called on the UN Human Rights Council to recognize the right to a healthy environment. Another option would be to get the UN General Assembly to pass a resolution similar to the 2010 resolution recognizing every person's right to water–though Schubert says the current political climate, in which some already-established rights are under attack, "is not very conducive" to an expansion of rights.

In the meantime, Terre des Hommes is working to build support for the idea through global civil society, from the grassroots upward. This year, the organization will host workshops on children's rights and the environment in every major region of the world; the first one will take place in May 2019 in Colombia. "Our vision is to come up with a declaration on the right to a healthy environment by the end of the project," Schubert says. "We hope it will be a forceful statement that can inspire further action at different levels, including standards-setting." Another goal is to convince national, state, and provincial governments to pass resolutions–or, even better, establish policies–that ensure equitable access to the natural world as well as protection from environmental degradation.

Schubert says that he sees "no distinction" between advocating for biodiversity, healthy ecosystems, and personal nature connection. When it comes to the environment, his work focuses on two children's rights: One is the right to play. The other is what he calls "the right to development" for the children of today as well as for future generations. "A connection with nature is in my view an underlying determinant of the right to development and health," he says. "Without it, children would have difficulties to develop properly."

So far, the effort to establish access to nature as a human right has focused almost exclusively on children. This makes sense as both science and political strategy. Advocates rightly see a children-focused strategy as their best chance for starting a discussion about a rights-based approach to time in nature. Since children are most vulnerable to interruptions in their development, their welfare is of a higher concern.

Yet this strategy has one obvious omission: adults. Neurological research has revealed that the human brain has impressive "plasticity"–that is, the brain can grow new neural pathways throughout a person's life span. Typically these neural adaptations come during specific windows of opportunity, often sparked by peak experiences. When confronted by stunning scenery or a close encounter with a wild animal, we use more of our senses than we do when, say, staring at a computer screen. Filled with wonder, we continue the developmental process begun in childhood.

Every human is part of nature, sprung from the womb of the earth. Yet human civilization has sought to separate itself from nature and in the process has caused a psychological and physical alienation that affects every species. Nothing good comes of this widening wound. To place access to nature into a framework of human rights and responsibilities offers the promise of closing the cut. It brings into focus the interdependence of all species, the "inescapable network of mutuality" that Martin Luther King Jr. devoted his life to creating among humans.

If we can agree that access to the rest of nature is fundamental to our humanity, to our very being, it could open the way to a renewed ecological solidarity–an intertwining of human rights and the rights of all nature. In saving the earth, we save ourselves.

NATURE BECOMES MOST REAL when it moves from the head to the heart. "What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never known a wren?" writes author and naturalist Robert Michael Pyle. It's a good line because it's true–and it's equally true for grown-ups.

Reversing biodiversity collapse and slowing climate change cannot be accomplished solely through politics, science, or technology. Success will require a far larger public constituency than exists today, one with a greater emotional and spiritual understanding of the interdependence of all species. While such understanding might be learned from a book, it can only be felt with one's feet on the ground.

To be clear, experiences in the natural world–whether in a wild forest or in an urban community garden–do not by themselves guarantee that people will care about protecting nature in the future. As children, the baby boom generation enjoyed significantly more access to the natural world than today's children and young people. The boomers did succeed in pushing environmental concerns onto the pages of newspapers and into the halls of Congress. At the same time, their unprecedented profligacy has pushed Earth systems to the brink of instability. Between 1970 and 2014, the global wildlife population shrank by 60 percent; global CO2 concentrations are above 400 parts per million and climbing. Regardless of how much time people have spent in nature, the destruction continues.

Closing the gap between human civilization and wild nature will require a set of values strong enough not only to protect endangered species and conserve energy but also to reshape health care, education, and whole cities, to conserve but also to generate new natural habitat–in effect, to regreen the earth.

The farmer-poet Wendell Berry writes of a war between two ethics: "The standard of the exploiter is efficiency; the standard of the nurturer is care. The exploiter's goal is money, profit; the nurturer's goal is health–his land's health, his own, his family's, his community's, his country's. . . . The exploiter typically serves an institution or organization; the nurturer serves land, household, community, place."

We don't have to look far to see these ethics in competition. During last winter's federal government shutdown, vandals trashed parts of Joshua Tree National Park in California. With park law enforcement reduced, some people toppled the fragile, threatened trees, raced four-wheelers across unspoiled desert (leaving tracks that could last hundreds of years), and flipped off people who objected. They were "accessing nature"–only to exploit it. Then came another response. Dozens of people volunteered to clean and repair the park as best they could. One of them was Rand Abbott, a paraplegic rock climber and advocate for Joshua tree conservation. He spent close to $5,000 on garbage bags and other supplies, then drove hundreds of miles to clean overflowing toilets and pick up garbage. His love for the desert and his bond with nature represented the ethic of care.

Where else can that ethic be learned if not in outdoor classrooms and natural schoolyards or on the trails of regional parks and in the deep wilderness? While doctors can offer such prescriptions, time in nature as a human right must be activated by democracy and available to all.

Recent developments across the world give reason for hope. Despite regulatory setbacks, pressure is building for a legislative response to climate change. Nature-based preschools, though still available mainly to more-affluent families, have increased in number by at least 500 percent since 2012. Urban agriculture is spreading fast, biophilic architecture is catching on, and wildlife corridors reach deeper into our cities. Families are planting their yards with native species that restore butterfly populations and migration routes.

The Scottish Wildland Trust reports that native woodlands cover a mere 4 percent of Scotland, and that, for children, the roaming distance from their home to play has shrunk considerably in 30 years. In 2005, a so-called right-to-roam law went into effect to address this issue and others. The Land Reform Act gives everyone a right to responsible access on most land and inland waterways throughout the country. Hikers can go just about anywhere on public and (most) private land if they treat the land and the owners of that land with respect. The law's advocates insist that rights and responsibilities are inseparable and that responsibilities must be taught and enforced. The right-to-roam law embodies the spirit of the words of poet Norman MacCaig that are etched on the side of the Scottish Parliament building: "Who possesses this landscape? The man who bought it or I who am possessed by it?"

Flowing in parallel to the demand for a human right to nature is another movement demanding that humans recognize the inalienable rights of nature. The effort to establish the rights of nonhuman nature has been slow, but it appears to be accelerating. In 2008, Ecuador changed its constitution to give nature "the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles." In 2010, Bolivia passed the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth, giving nature rights equal to those of humans.

And in 2017, the New Zealand Parliament declared that the country's third-largest river, the Whanganui, has the same legal rights as a person. This made the Whanganui the first river in the world to be recognized as a living entity. The designation resulted from a 140-year campaign by New Zealand's Maori, who view the river as essential to the well-being of people and all the lives that depend on it for survival. The bill gave the river all the rights, duties, and liabilities that come with personhood; the river can now be represented in court proceedings. Two guardians will act on the river's behalf: a member of the Indigenous Whanganui Iwi community and a representative of the Crown.

Just as the Whanganui now possesses legal rights, all the plants and animals touched by the Whanganui–including people–have a right to enjoy that river. And if the river is not healthy? Then each and every one of those rights becomes meaningless.

The Catholic priest Thomas Berry, whom Newsweek called one of the world's most provocative eco-theologians, anticipated and aspired to this evolution of ethics. In his book The Great Work, he wrote, "The present urgency is to begin thinking within the context of the whole planet, the integral Earth community with all its human and other-than-human components. When we discuss ethics, we must understand it to mean the principles and values that govern that comprehensive community." Berry believed that "a degraded habitat will produce degraded humans." He also believed that "everything has a right to be recognized and revered. Trees have tree rights, insects have insect rights, rivers have river rights, and mountains have mountain rights."

Those lines were written 20 years ago, and the hour has grown later since. If the environmental movement is to flourish, it must ensure that people of all races, cultures, income levels, and zip codes have an equal chance to connect with the rest of the natural world. The concept of social capital can no longer apply to only one species; it should apply to all species. We can truly care for nature only if we see ourselves and nature as inseparable, only if we love ourselves as part of nature, only if we believe that we, our children, and our descendants have a right to the gifts of undestroyed nature.

Reconnecting the human species with the rest of the world is the great work of the 21st century, as Berry put it. Some of this work can be done by Congress or by the UN, by business and education and the great conservation organizations. The rest of it will be accomplished through small and meaningful acts, no more complicated than stepping outside among the trees with the people we love. That's what Dr. Razani encourages her patients to do.

"A lot of people are concerned that kids are spending too much time on computers," she says, "but what I see is parents and kids yearning for each other." She often begins a family session by asking the parents or grandparents what their childhood was like and about a special place in nature that they remember. "The room becomes very quiet. Sometimes the grandparents start to cry." And then she takes all of them to the park, together.

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2019-3-may-june/feature/outdoors-for-all-nature-is-a-human-right

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)